Throughout history, tyrannical and absolute governments has been the norm for humanity, not the exception. While under the yoke of despotic and even arbitrary rule, it became clear to many people that such governments are not only unnecessary, but also incredibly harmful, especially considering their parasitical nature. It was with this understanding that the philosophers during the Age of Enlightenment began to illustrate the true relationship between mankind and its governments.

Classical liberalism posits that the proper relationship between an individual and government is one based on the consent of the governed. Limited powers are delegated to the government by its citizens, and thus is essentially a night-watchman State, regardless of its structure. Absent such consent, trespassing beyond the limited powers, or otherwise violating property rights systematically, ipso facto transforms any such night-watchman State into an arbitrary and/or despotic, and thus tyrannical, government, that as such, deserves to be altered or abolished.

Before government, mankind lived in a state of nature, which is a living condition of liberty, equality, and perfect freedom, subject only to the law of nature. Locke described the state of nature another way:

“The natural liberty of man is to be free from any superior power on earth, and not to be under the will or legislative authority of man, but to have only the law of nature for his rule.”

Needless to say, such natural liberty does not require a government. This way of life also entails total responsibility, especially when it comes to the provision of justice, which necessarily entails that every individual bears the duty of enforcing the law of nature by punishing those who violate it, in proportion to the degree of their transgression. Because such a way of being can become an unbearable encumbrance, most people chose to abandon it in exchange for the convenience of a civil society; therefore, it could be said that the state of nature is far from being an ideal condition of life, and merely a transitional phase from one state of society to another.

Social contracts originally arose from private agreements between individuals for mutual long-term gain. The relationships between husband and wife, parent and child, and even master and servant are all types of social contracts (in the context of the last relationship type, it would be more accurate to think of them as employer and employee, since the servant in this case agreed to exchange labor for wages, and is thus not a slave, and least not in the classical sense of the term). Of course, some political dissidents may raise concerns about the coerciveness of some of these arrangements, but what they must remember is that contracts are not limited to explicit consent, but in certain circumstances can be held as valid if they are not explicitly objected to, as is the case with tacit consent (better known as acquiescence). Such social contracts are intrinsically based on the consent of the governed, including those that are tacit.

For instance, because a child benefits from parental care, but neither explicitly consents nor explicitly objects to it, I think it is more than fair to say that he has acquiesced to his parents’ rule over him (provided of course there is no abuse of the social contract on the parents’ part). Locke describes the nuances of consent thusly:

“Every man being, as has been shewed, naturally free, and nothing being able to put him into subjection to any earthly power, but only his own consent; it is to be considered, what shall be understood to be a sufficient declaration of a man’s consent, to make him subject to the laws of any government. There is a common distinction of an express and a tacit consent, which will concern our present cause. No body doubts but an express consent, of any man entering into any society, makes him a perfect member of that society, a subject of that government. The difficulty is, what ought to be looked upon as a tacit consent, and how far it binds, i.e. how far any one shall be looked on to have consented, and thereby submitted to any government, where he has made no expressions of it at all. And to this I say, that every man, that hath any possessions, or enjoyment, of any part of the dominions of any government, doth thereby give his tacit consent, and is as far forth obliged to obedience to the laws of that government, as any one under it; whether this his possession be of land, to him and his heirs forever, or a lodging only for a week; or whether it be barely travelling freely on the highway; and in effect, it reaches as far as the very being of any one within the territories of that government.”

In other words, because you enjoy the physical infrastructure and the free market, you must obey the government, assuming that it isn’t tyrannical (thus violating its social contract with you as a guardian of your liberties). Now, at this point, one may wonder why not just live in a state of nature and avoid the whole mess? Well, considering that government statutes provide a semblance of codified property rights (whenever they aren’t being tyrannical), as well as the fact that theoretically some social contracts would exist without government (at least initially, as is the case with the family), it would sort of stand to reason that, absent the free market production of security and arbitration services, the establishment of a government is inevitable, and thus the best you can hope for is some variation of the night-watchman State; ergo, somehow reverting to living in a state of nature without just cause is nothing more than an exercise in futility.

How then, is one to determine whether he lives under a tyrannical government? It would be wise to determine whether a state of war exists first:

“Men living together according to reason, without a common superior on earth, with authority to judge between them, is properly the state of nature. But force, or a declared design of force, upon the person of another, where there is no common superior on earth to appeal to for relief, is the state of war: and it is the want of such an appeal gives a man the right of war even against an aggressor, tho’ he be in society and a fellow subject…[t]he state of war is a state of enmity and destruction; and therefore declaring by word or action, not a passionate and hasty, but a sedate settled design upon another man’s life, puts him in a state of war with him against whom he has declared such an intention, and so has exposed his life to the other’s power to be taken away by him, or any one that joins with him in his defence, and espouses his quarrel; it being reasonable and just, I should have a right to destroy that which threatens me with destruction; for, by the fundamental law of nature, man being to be preserved as much as possible, when all cannot be preserved, the safety of the innocent is to be preserved: and one may destroy a man who makes war upon him, or has discovered an enmity to his being, for the same reason that he may kill a wolf or lion; because such men are not under the ties of the commonlaw of reason, have no other rule, but that of force and violence, and so may be treated as beasts of prey, those dangerous and noxious creatures, that will be sure to destroy him whenever he falls into their power.”

Since “tyranny is the exercise of power beyond right” in violation of the Law, then I think it is more than fair to say that tyranny, by definition, creates a state of war, just as muggers and rapists create a state of war with their intended victims. If, however, an individual happens to discover that he lives under a tyranny, is there any way he can choose to revert to living in a state of nature while, more likely than not, suffer from being even peripherally effected by tyrants? Only insomuch as he can retreat from a state of society by withdrawing his consent to be governed as much as realistically possible; any effort to totally abdicate the use of the physical infrastructure is literally impossible at this juncture, especially considering that there are no more frontiers on the land left to go explore and settle, even as a form of escape from tyrannical government.

As a blessing in disguise, this exponentially increases the significance of the need for dissolving the government, for governments can be dissolved from within, as well as by any branch of it that acts contrary to the trust placed into it by the people. To describe the latter variation, Locke said:

“[W]henever the legislators endeavour to take away, and destroy the property of the people, or to reduce them to slavery under arbitrary power, they put themselves into a state of war with the people, who are thereupon absolved from any farther obedience, and are left to the common refuge, which God hath provided for all men, against force and violence. Whensoever therefore the legislative shall transgress this fundamental rule of society; and either by ambition, fear, folly or corruption, endeavour to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other, an absolute power over the lives, liberties, and estates of the people; by this breach of trust they forfeit the power the people had put into their hands for quite contrary ends, and it devolves to the people, who have a right to resume their original liberty, and, by the establishment of a new legislature, (such as they shall think fit) provide for their own safety and security, which is the end for which they are in society.”

Obviously, the same applies to the executive, in that his legitimacy is forfeited the second he (or any of his subordinates) breaches that trust. Yet, all of this begs the question as to what are the necessary conditions for engaging in the right of revolution? Locke describes it thusly:

“Great mistakes in the ruling part, many wrong and inconvenient laws, and all the slips of human frailty, will be born by the people without mutiny or murmur. But if a long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the people, and they cannot but feel what they lie under, and see whither they are going; it is not to be wondered, that they should then rouze themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands which may secure them the ends for which government was at first erected; and without which, ancient names, and specious forms, are so far from being better, that they are much worse, than the state of nature, or pure anarchy; the inconveniences being all as great and as near, but the remedy farther off and more difficult.”

Put another way, if you can prove that the tyranny in question is systematic and not able to be reversed by way of reform, then nobody should be surprised when revolts break out. I also think, gauging from the wording, where Thomas Jefferson got his inspiration from when he penned that revered declaration.

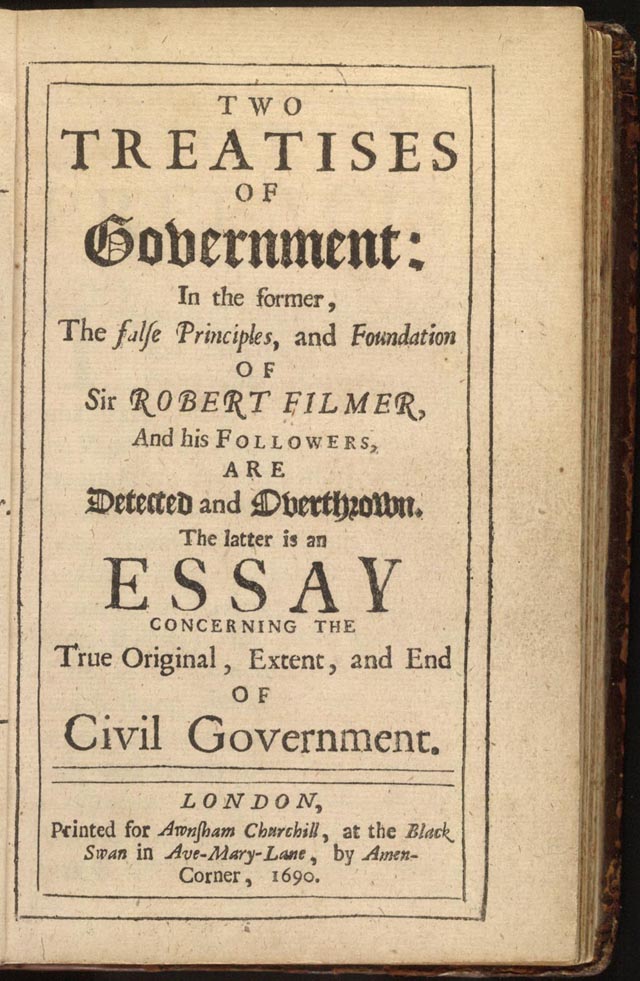

John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government is a ground-breaking philosophical work of literature straight from the father of classical liberalism. While I personally take issue with Locke the idea that a state of society necessarily requires a government, I can still appreciate how his love of liberty permeates the entire text, even to the point of justifying genuine revolutionary action. Overall, this is a must read for all political dissidents who desire a foundational understanding of the power of non-compliance, the duty of civil disobedience, and of the formal withdrawal of consent to be governed via a Declaration of Dissolution of Government.